The First Astronomers

By Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

By Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

RSV Science Engagement

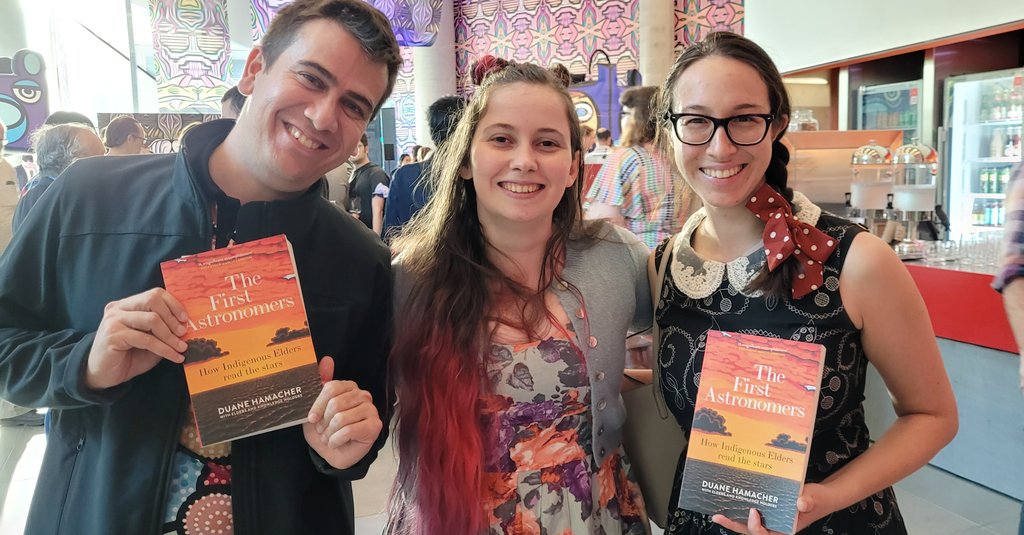

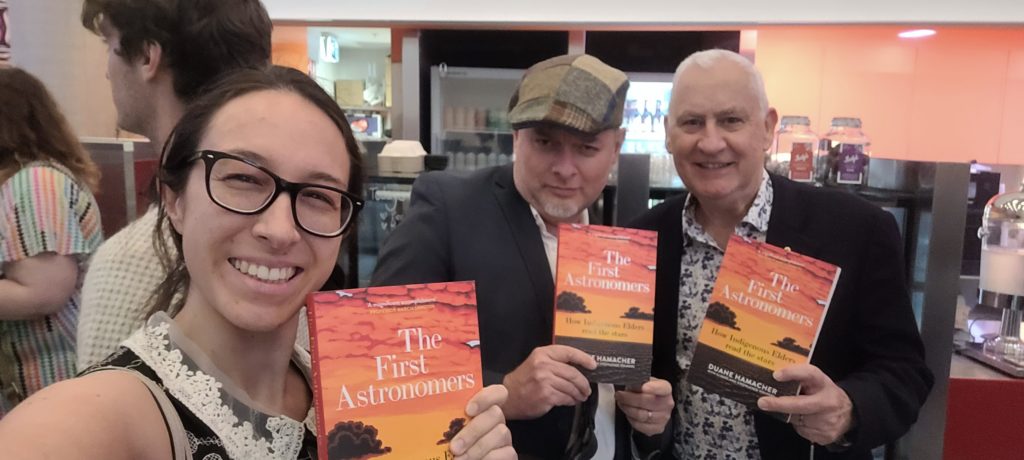

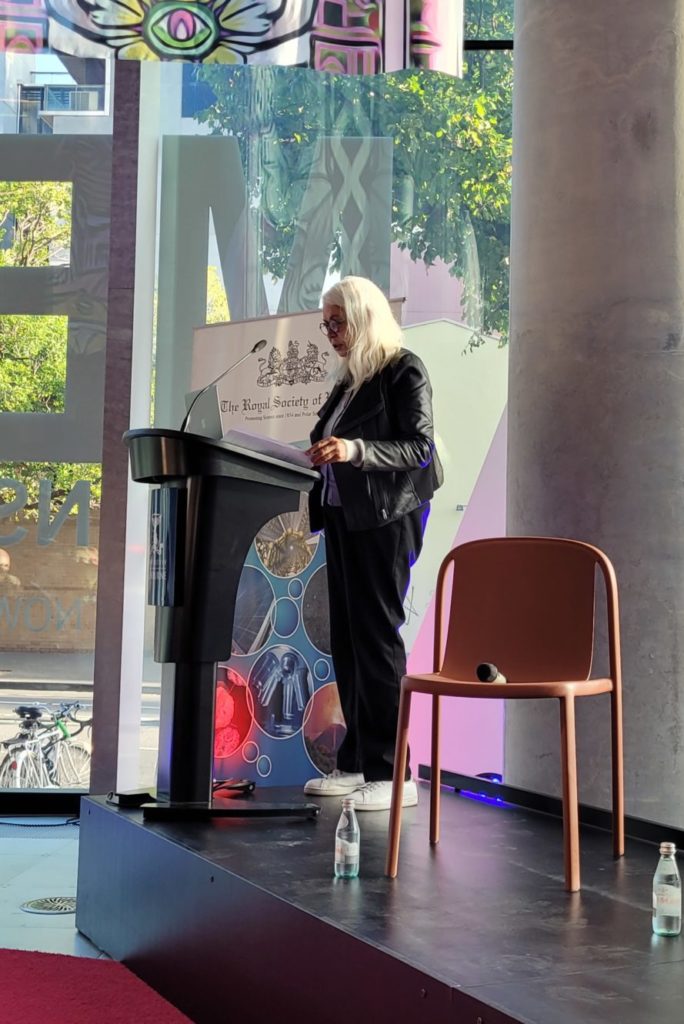

This article follows the book launch of The First Astronomers: How Indigenous Elders Read the Stars, hosted by the Royal Society of Victoria and the University of Melbourne at Science Gallery Melbourne on 9th March 2022. The event featured N’arweet Dr Carolyn Briggs AM, Professor Marcia Langton AO, Uncle Ghillar Michael Anderson, and Associate Professor Duane Hamacher, with MC Professor Alan Duffy.

‘[The First Astronomers] is going to change your view of science and how it is practiced,’ says Professor Marcia Langton. ‘There’s no going back.’

We no longer look to the night sky to predict the weather, forecast seasons, or know when to plant our gardens or harvest. Living in the bright light of major cities, most of us cannot even see the Milky Way clearly.

But First Nations Elders around the world still maintain the knowledge of how to read the skies and understand its connection to land.

Indigenous astronomy is the first astronomy. It existed long before the Babylonians, Greeks, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. They have long known about the planets, understood the movement of the Sun, celebrated eclipses in ceremony, and have stories of the Big Bang. For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have been observing the land, sea and sky.

There is no single First Peoples astronomy, as astronomical traditions vary largely between different language groups. First Nations groups are diverse yet unified. According to N’arweet Carolyn Briggs, all share a connection across the lands and waters of their ancestors. These ties have not been severed since Creation, despite the dispossession, displacement, and discrimination they have experienced over the past 200 years.

Astronomy is embedded within their traditions and cultures. They assign meaning to astronomical phenomena that informs Law and serves as a foundation for the songs, dances, and oral traditions passed from generation to generation.

N’arweet Carolyn shared the Boon Wurrung Wurrungi biik, laws of the land. The first law is Yulendj: the responsibility for knowledge, to maintain and pass it down to be used by future generations. The First Astronomers shares some of that knowledge so that it can be respected and live on as part of science.

Associate Professor Duane Hamacher is at the intersection of Indigenous Knowledge and modern science. He came to Australia to complete a Masters in astrophysics and a PhD in Indigenous studies. At astrophysics conferences, he sometimes struggled to convince peers that Indigenous Knowledge was anything more than folklore.

For years, he has been guided by Elders to share their knowledge and change the history and philosophy of science and how we see it. In The First Astronomers, Duane showcases their wisdom and shows how these living systems of knowledge challenge conventional ideas about the nature of science. Indigenous science is dynamic, adapting to changes in the land, seas and skies. Built on careful observation over 65,000+ years.

Professor Marcia Langton has been advocating for the incorporation of Indigenous Knowledge in the classroom for years, but it was not easy in the beginning. She led a project that provides resources to assist teachers in implementing the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures across different learning areas of the Australian curriculum. The First Astronomers is the book that she had wanted for the teachers and students she has visited across the country.

But of course, there is always more to learn. ‘What this book represents is only a tiny bit of our stories…our knowledge,’ says Uncle Ghillar Michael Anderson. A Senior Law Man, Elder and leader of the Euahlayi Nation, Uncle Ghillar is one of the six Elders who co-authored the book. He learned his knowledge of the stars from women – as did many others – and would like to see their knowledge featured too. (Perhaps there is an opportunity for a sequel?…)

Uncle Ghillar emphasised that this is only the tip of the iceberg. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people understandably want to protect their knowledge from manipulation, abuse, bastardisation, or prosecution. Nor will the wider community ever be able to fully comprehend and understand it all. With different cultures, backgrounds and world views, we all have different values when it comes to land. The wider community may only ever be able to understand Indigenous Knowledge at “a kindergarten level” – but that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try.

Duane hopes that the book will encourage Western astronomers to treat Indigenous Knowledge with respect. What Western astronomers were uncovering in the last several centuries was “old knowledge” to First Nations Australians. The book demonstrates how respectful collaborations can drive exciting and innovative solutions to global challenges that impact our shared future. “Rarely is a book of such importance published’, says Marcia.