Our Mesozoic Menagerie

By Catriona Nguyen-Robertson and Scott Reddiex

RSV Science Communications

This article follows a presentation by Dr Stephen Poropat (Swinburne University) to the Royal Society of Victoria on the evening of Thursday, 8th March 2018 titled Our Mesozoic Menagerie: Australia’s Dinosaurs.

Imagine the knowledge encompassed in 180 million years of history lying beneath the Earth’s surface.

The Mesozoic Era – The Age of Dinosaurs – is comprised of the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, spanning from 252 to 66 million years ago (Mya). The duration of this era was so long that in 2018 we are closer in time to the Tyrannosaurus rex (66 Mya) than the T. rex was to Stegosaurus, which roamed the Earth about 150 Mya.

The Mesozoic is bounded by mass extinctions: it began following the Permian-Triassic extinction event, in which 97% of all life on the planet was lost, and ended with the more well-known Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, that wiped out 75% of species on Earth and marked the definitive end to the age of dinosaurs. Interestingly, while the latter event can often be represented as the traumatic end to the dinosaurs at their peak, their numbers had been in steady decline for nearly 40 million years prior to a large asteroid striking Earth, boiling the atmosphere and throwing up black dust that blocked the Sun’s light and heat for months.

Much less traumatic than a rock from the sky, Dr Stephen Poropat was struck with a love of dinosaurs from a young age, after being gifted a book on dinosaurs in grade one by his neighbours. His path to successfully pursuing palaeontology (‘where biology and geology meet’) as a career was in part thanks to his high-school biology teacher, Penny Crossman, at Whitefriars College in Donvale. Dr Poropat told us how she was able to engage with the students and teach complex concepts by teasing them apart and explaining them. This, he says, ‘broadened his horizons’, and set him up with the tools to pursue a Bachelor of Science/Bachelor of Arts, followed by a PhD, at Monash University.

Our evidence for the existence of the different dinosaurs that lived in prehistoric Australia comes from fossilised animal remains and other records of life, such as fossilised footprints. Specific conditions are required for fossilisation to occur, which means that not all life-forms from the Mesozoic Era are preserved, but they are all we have to determine the types of animals that existed during this time. As Dr Poropat puts it, ‘we need the right rocks!’.

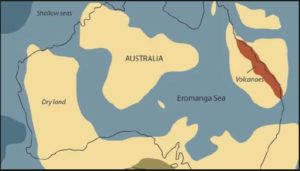

What is now Australia was a very different place during the Mesozoic Era. Scattered throughout the continent, the ‘right rocks’ from all three of the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous periods can be found. At the beginning of the Triassic period, all of the continents were combined in a supercontinent called Pangaea. The Australian landmass during this time was bounded by Antarctica to the south and India to the west, and sat much closer to the South Pole than it currently does. Over the course of the era, a body of water called the Eromanga Sea covered much of the continent. The prehistoric waterways helped to form the right conditions for dinosaurs to flourish, and subsequently to be preserved in what is now the arid inland of Australia.

The first dinosaurs began to appear in the late Triassic, around 230 Mya, however we have limited fossil records of dinosaurs from this period because of their scarcity. What we do have from the Triassic are fossils of temnospondyl amphibians – ‘Triassic fish’ – found in every Australian state and territory, as well as the oldest dinosaur footprint (~220 Mya) uncovered in a coalmine in Dinmore, Queensland.

From the Jurassic period, only three dinosaur skeletons have been found in Australia, along with a few sites of preserved footprints dispersed across Queensland and Western Australia. Most of our dinosaur fossils instead come from the Cretaceous period, when large numbers of dinosaurs such as sauropods (herbivores), theropods (larger carnivores) and aquatic plesiosaurs roamed the Australian land and waterways. Many dinosaur fossils from this period have been discovered in the Winton Formation – a geological deposit in central-Western Queensland from the Late Cretaceous period that contains the remains of dinosaurs that lived 98-95 Mya.

Dr Poropat’s scientific journey has been closely connected with the Winton Formation, and with David Elliot, co-founder of the nearby Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum. David and his wife Judy raise sheep on their property in Winton, where one fortuitous day he stumbled across a small pile of fossilised bone fragments on the ground. Following this initial discovery, the site has since been excavated to yield many fantastic finds – in particular, the remains of one of the most complete sauropod dinosaurs ever found in Australia, nicknamed ‘Wade’, after Dr Mary Wade of the Queensland Museum.

After a decade of reconstruction work, Dr Poropat identified Wade as a new species of plant-eating sauropod. He formally named it Savannasaurus elliottorum, in honour of the Elliots and the savannah country of Central Queensland where it was discovered. It was not the only dinosaur to be found on the Elliot’s property: last year, David’s son Bob Elliot discovered ‘one of the most amazing sauropods ever found in Australia’. While Dr Poropat and his team are currently still preparing and studying the fossils, it appears to reveal the gut contents of this creature’s last meal – potentially being the first concrete evidence in the world for a dinosaur’s diet.

Another owner of a Winton sheep station, Keith Watts, also discovered dinosaur fossils on his property in 1974. The bones were collected by Dr Mary Wade and Andrew Elliot and were found to be the first Cretaceous sauropod discovered in Australia. The location of the find was unfortunately lost until 2004, when Dr Poropat used clues from a roughly drawn map, details of a sign that had previously marked the site, and a flyover in local mayor’s helicopter to rediscover the area, and he was able to find more remains of the now-termed Wintonotitan wattsi.

In the same area, Australovenator wintonesis (nicknamed ‘Banjo’), Australia’s most complete theropod dinosaur was discovered amongst the remains of a sauropod dinosaur, Diamantinasaurus matildae (nicknamed ‘Matilda’). While the exact cause of Banjo’s death remains unknown, Dr Poropat postulates that Banjo was killed while preying on a bogged Matilda, however what is clear is that the two were trapped in a drying waterhole and preserved together.

Lastly, Dr Poropat was fortunate enough to study the Lark Quarry Stampede. 95 Mya, herds of two-legged dinosaurs came to drink at a lake when a large, carnivorous theropod is thought to have spooked them into a stampede. At least 150 small dinosaurs of different kinds left their footprints behind on a site as large as a tennis court, and Dr Poropat believes that there may still be more footprints extending beyond and below the area.

Dr Poropat has been digging up dinosaur bones for over a decade, and his studies depend on the serendipity of discoveries, When asked where his top place to dig with unlimited time and money was, he chose three: Koonwarra, Victoria, where he has previously discovered feathers, fish, invertebrates, and plants, but believes that there is much more to be found; Talbragar, NSW, Australia’s only good Late Jurassic vertebrate fossil site; and Miria Marl, WA, the only site in Australia to have yielded vertebrate fossils from the end of the Dinosaur Age.