Are We Living in Liveable Cities?

by Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

RSV Science Communications Officer

This article follows a presentation to the Royal Society of Victoria on 10th June 2021 titled “Liveable cities for all: are we there yet?” delivered by Professor Billie Giles-Corti (RMIT University). All images used here are extracted from her presentation.

This article follows a presentation to the Royal Society of Victoria on 10th June 2021 titled “Liveable cities for all: are we there yet?” delivered by Professor Billie Giles-Corti (RMIT University). All images used here are extracted from her presentation.

Melbournians are proud of having been ranked the most liveable city for seven consecutive years – although we have recently dropped slightly in the rankings. But what makes a liveable city? Professor Billie Giles-Corti investigates measures of liveability and assesses whether we are actually creating liveable cities that support healthy and sustainable lifestyles for both individual and planetary health.

The combination of rapid urbanisation and population growth is growing concern. By 2050, 68% of the global population will be living in cities. ‘We have a problem – we need to carefully think about how we are planning our cities,’ says Billie.

The population rise would mean that around 1.6 million new residences would need to be built, it would put pressure on our resources and infrastructure, and more people packed together would severely increase traffic congestion. A problem we tend only to think about when stuck in a traffic jam ourselves, congestion is quite economically expensive. Infrastructure Australia estimates that by 2030, traffic congestion will reach $53 billion per year in lost productivity. Our cities will not be equipped to support us if nothing changes.

For over three decades, Billie has worked towards solutions. A Distinguished Professor at RMIT University and Director of the Healthy Liveable Cities Lab, she leads a multi-disciplinary research studying the impact of the built environment on health and wellbeing.

Ten years ago, when Billie first came to Melbourne, she was challenged by her colleague Dr Ian Butterworth to provide evidence that good urban planning is connected to health in a way that could influence policy.

They looked into the social determinants of health: the economic, social and political systems that shape conditions of daily life. They believed that health is linked to access to reliable public transport, health food, local parks, places of leisure, and friends and family. While it may seem obvious that these factors play into our physical and mental health, to bring government officials on board, Billie and Ian needed supporting data. They therefore defined “liveability” to include these social determinants that create good or poor health.

They looked into the social determinants of health: the economic, social and political systems that shape conditions of daily life. They believed that health is linked to access to reliable public transport, health food, local parks, places of leisure, and friends and family. While it may seem obvious that these factors play into our physical and mental health, to bring government officials on board, Billie and Ian needed supporting data. They therefore defined “liveability” to include these social determinants that create good or poor health.

Liveability was a highly valued concept at the time and would hence be more appealing to policymakers like the Minister for Transport Infrastructure. Having a compact city is all well and good, but to avoid traffic congestion and resulting air quality and noise problems, land use and transport need to be considered together. There is little point in building houses at the fringes of cities that are not well connected to amenities, services, and places of work. It becomes unaffordable and unsustainable if people have no way of getting around except to drive.

‘If you want to have a compact city – which we need on from a global perspective – we also need to manage traffic.’

By placing bike paths near train stations, Billie has seen that more people are encouraged to take public transport and accumulate more incidental exercise as they walk or cycle to/from stations. To encourage this sustainable mobility, we require a shift from the traditional transport planning approach. If we want more people using public transport instead of cars to get around, the infrastructure needs to be better.

If we want people to change, they need to be supported by polices that are well-implemented.’

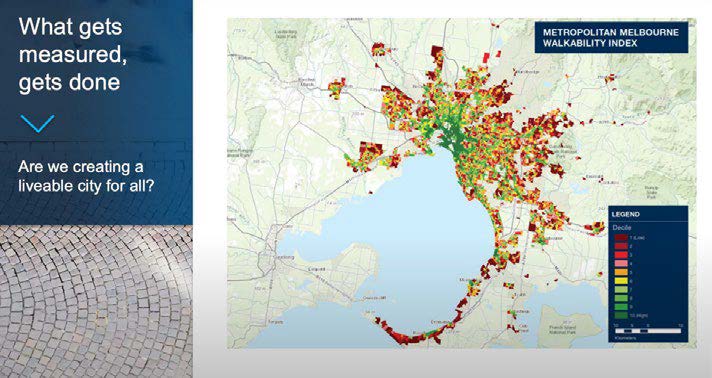

Billie looked at the policies that she wanted to influence and structured studies to assess the built environment in Metropolitan Melbourne around them. She found that there were variations in access to health-promoting amenities based on location: inner suburbs had greater walkability and connectivity, more people getting around on foot, bike or public transport, and better access to social infrastructure compared to outer suburbs. In contrast, heart attack rates were greater in areas with poorer access and connectivity, showing a direct link between location, built environment, and health.

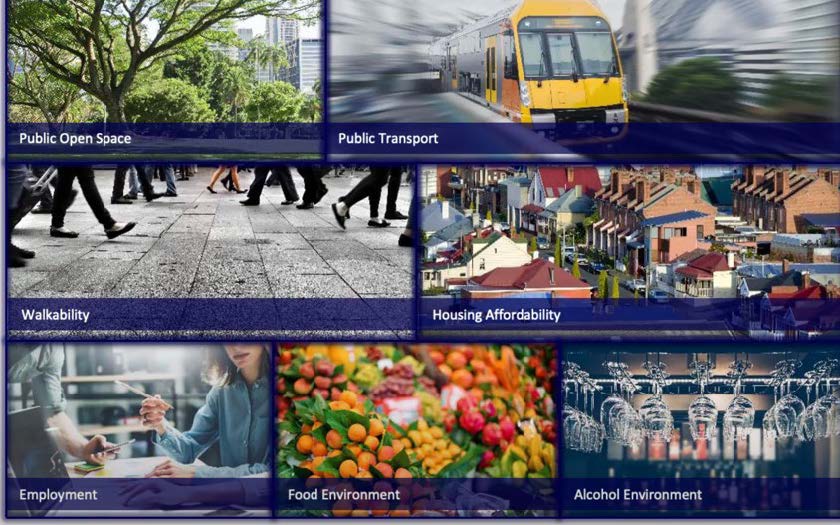

Following the success of her studies in Melbourne, Billie set about creating the first baseline measure of liveability in all Australian capital cities. Over five years, her team mapped liveability indicators and urban policy implementation in a report, ‘Creating liveable cities in Australia’ (published 2017). They assessed seven domains of urban liveability and found that, in many cases, government planning policies were failing to deliver them equitably within and between cities. No capital city performed well across all seven.

‘Climate change is the biggest threat to human health – this isn’t a dress rehearsal,’ says Billie.

Greenhouse gas emissions produced by transport are warming the planet and are one of the main causes of air pollution, which kills 4.2 million people worldwide per year. Climate change has also seen an increase in the length and intensity of bushfire seasons which impacts the health of people and ecosystems alike. During the 2020 bushfires, air pollution (PM2.5) levels in Sydney and Melbourne reached levels that were classified as hazardous by the World Health Organisation. By moving towards more sustainable mobility and having fewer cars on the road, we can reduce the impact of our daily travel on the environment, and it will also benefit our health.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a reminder of just how important city planning is. With Melbourne’s lockdown restricting people to remain within a 5km radius from their homes, those who had shops, parks, and family and friends nearby were more likely to manage better. We still have a way to go in terms of building liveable cities in Australia, but Billie hopes that has acted as a wake-up call.

Billie’s work highlights the need for consistent evidence-informed urban planning policies and integrated planning of housing, transport, land use and infrastructure to optimise health outcomes and reduce liveability inequities. We need people like Billie advocating for the implementation of policies that improve urban liveability, thereby improving the health and wellbeing of the community, and ensuring that our quality of life is maintained as our cities continue to grow.