The RSV’s Mystery Portrait – Solved!

As a small, volunteer-led organisation for most of our history, our capacities for record keeping have waxed and waned; the details of our past are most faithfully recorded in the memories of our members, past and present, and the time for an update to our official histories is most definitely overdue.

As a small, volunteer-led organisation for most of our history, our capacities for record keeping have waxed and waned; the details of our past are most faithfully recorded in the memories of our members, past and present, and the time for an update to our official histories is most definitely overdue.

We do have plenty of resources to offer the intrepid historian. The Royal Society of Victoria’s long history of convening the science community and promoting science in our state has contributed to a burgeoning archive of documents and some rare books deposited with the State Library of Victoria, who provide public access for the benefit of researchers. Meanwhile, we still maintain quite a few curious documents and objects from our past, squirrelled away in various shelves, cabinets and cupboards, our small archive room and the squeezy spaces beneath the raked seating of the Ellery Theatre.

One such object is this portrait from the mid-20th century, painted in 1961 by Orlando Dutton, depicting a scholar, his medals and a microscope, without any name provided. Current and recent Councillors have not definitively identified the sitter, although there was some speculation about him being Sir Frank Marfarlane-Burnet OM AK KBE FRS FAA FRSNZ. Speculation on the medals depicted have ranged from Mac Burnet’s Nobel prize (1960) to his inaugural Australian of the Year trophy (1961).

Stumped, we put out a call to the science community to help us solve the puzzle, and we’ve had an enormously helpful response through email and social media channels.

Stumped, we put out a call to the science community to help us solve the puzzle, and we’ve had an enormously helpful response through email and social media channels.

Not Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet

Many have suspected/asserted that the portrait is of Mac Burnet, and we shared the portrait broadly in that context. The closest likeness of Sir Mac to the portrait that we could find is provided to the right, from 1959.

However, a welcome email from RSV Fellow (and Medallist) Professor Sir Gustav Nossal puts that theory to rest:

“I am Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s successor as Director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

As such, I knew Sir Mac very well for over 30 years and also had the chance to view several portraits of him painted down the years.

I am quite sure that the Mystery Portrait on page 13 of your November Newsletter is not of Sir Mac.

It is obviously a good painting and therefore probably a good likeness of the sitter.

It genuinely isn’t at all like Sir Mac (at any age).

Is there a possibility that it is Lord Casey?

I only knew him as an older man but the faint moustache, forehead and hair suggest the possibility.

Best of luck!

Yours sincerely

Gus Nossal.”

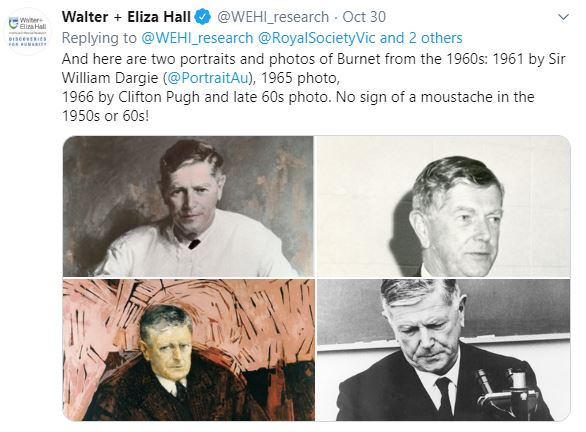

Further leads on Twitter from our colleagues at WEHI (right) support this position. Sir Mac was not one to cultivate a moustache, plainly, and his features were distinctly emphasised by artists Dargie and Pugh in a manner entirely dissimilar to the Dutton portrait’s subject.

Orlando Henry Dutton (1894 – 1962)

So, let’s take a look at the artist. Genealogist Jan Worthington took a good, hard look and advises:

“Orlando Henry Dutton was not a portrait painter. He was primarily a stone mason and sculptor although he did paint still life. He was born in Walsall, Staffordshire, England on 1 April 1894, the son of Henry and Eliza Priscilla Dutton, and lived there with his family until the age of 20 years when he served in the military during World War 1 in England. He married Emma Jane Hancock on 15 August 1922 in Adelaide, South Australia and they did not have any children who could be contacted regarding the painting. Emma Jane died in England shortly after they arrived on one of their trips together.”

“Orlando served in the 2nd Australian Imperial Force in WW2 and enlisted at Caulfield, Melbourne. After the War, Emma and Orlando took several trips to England, where he entered his paintings and sculptures in various exhibitions as a member of the Australian Artists Association. In 1957 he exhibited three works in the Imperial Institute Art Gallery, London with other Australian artists. He returned from another trip in 1958 and again in 1960 and was described on the passenger lists as a “retired sculptor.””

“Orlando drowned in the Yarra River at Fairfield on 17 August 1962.”

Here’s what Leonie Kirchmajer has uncovered for us:

“From what I could find about Orlando Dutton, he was primarily a sculptor who was employed as an assistant to Edwin Sherbon Hills during WWII when he was commissioned by the Australian Army to create a relief model of northern Australia and New Guinea to aid in defence planning. I found the record of a photo (though not the image itself) of staff of the University of Melbourne’s Department of Geology and Mineralogy and the CSIR Mineragraphic Section from 1946. The list of names included Orlando Dutton, as well as the following recipients of the David Syme medal: Frederick Singleton, Edwin Sherbon Hills, Frank Stillwell, and George Baker. I found reference to a portrait of Frank Stillwell by Orlando Dutton that hangs in the Stillwell Room of the Graduate Union of the University of Melbourne. Given he was mainly a sculptor and that the only portrait references I could find were his portrait of Frank Stillwell and a self-portrait, perhaps it’s more likely the subject of this portrait is someone he knew personally.”

Given the year painted (and the artist’s dominant practice of sculpture), this is most likely Orlando Dutton‘s final portrait, as he tragically drowned the following year in 1962. He was an artist of some standing in Victoria and had been the President of the Victorian Arts Society from 1946-47. So as Sir Gus asserts, it’s quite a good painting, and most likely an accurate likeness of the sitter.

Given the year painted (and the artist’s dominant practice of sculpture), this is most likely Orlando Dutton‘s final portrait, as he tragically drowned the following year in 1962. He was an artist of some standing in Victoria and had been the President of the Victorian Arts Society from 1946-47. So as Sir Gus asserts, it’s quite a good painting, and most likely an accurate likeness of the sitter.

The Robes

Next, let’s consider the sitter’s doctoral cap and gown. Theories abounded about the University of Dublin, as well as both UK and local medical degrees, largely due to the green elements. We put a call out to the Burgon Society via Twitter – they are a UK-based non-profit founded to “promote the study of academical dress in all its aspects – design, history and practice.”

Very helpfully, the Burgon Society confirms “the sitter is wearing University of Melbourne robes.” Thank you!

The Medals

These were shared in as much detail as the portrait could allow us, and were subject to broad speculation! The outlying theories were various medical medals conferred overseas, while the dominant contenders were:

These were shared in as much detail as the portrait could allow us, and were subject to broad speculation! The outlying theories were various medical medals conferred overseas, while the dominant contenders were:

- The Nobel Prize (for something) – essentially, related to Marfarlane Burnet.

- The inaugural Australian of the Year Trophy – again, related to Macfarlane Burnet.

The Numismatic Association of Victoria took a shot at the medals, sensationally sharing this gorgeous award from the RSV’s essay competition of 1860 – but obviously, not a contender for those in the portrait.

Following our own frustrating and ultimately fruitless search through online archives, our colleagues at WEHI were able to help us out with an image of the inaugural Australian of the Year Medallion awarded to Sir Mac in 1960 (right). An amazing, historic artefact, it’s quite clearly not the medallions captured in the portrait. Images of Nobel prizes from this era also bear scant resemblance. Given the earlier deliberation about ruling out Sir Mac, we likewise rule out the Nobel and the Australian of the Year.

Following our own frustrating and ultimately fruitless search through online archives, our colleagues at WEHI were able to help us out with an image of the inaugural Australian of the Year Medallion awarded to Sir Mac in 1960 (right). An amazing, historic artefact, it’s quite clearly not the medallions captured in the portrait. Images of Nobel prizes from this era also bear scant resemblance. Given the earlier deliberation about ruling out Sir Mac, we likewise rule out the Nobel and the Australian of the Year.

The Case for Dr George Baker (1908 – 1975)

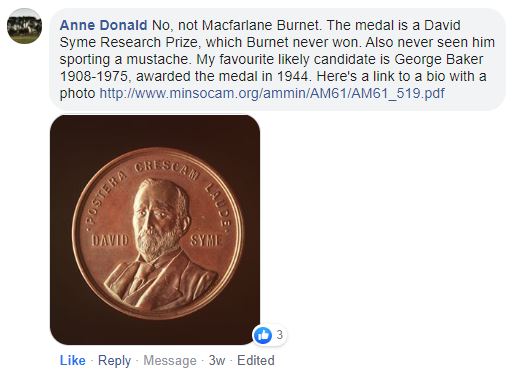

Anne Donald first established the link between the medals and Dr George Baker in a Facebook post, referencing a document from the Mineralogical Society of America. She identifies the bronze medallion as the University of Melbourne’s David Syme Research Prize, which correlates with Leonie Kirchmajer’s findings concerning the artist, Orlando Dutton, and his associations with the University’s mineralogists and Prize winners. Certainly, the Syme medallion aligns favourably with the bronze medallion in the portrait.

Anne Donald first established the link between the medals and Dr George Baker in a Facebook post, referencing a document from the Mineralogical Society of America. She identifies the bronze medallion as the University of Melbourne’s David Syme Research Prize, which correlates with Leonie Kirchmajer’s findings concerning the artist, Orlando Dutton, and his associations with the University’s mineralogists and Prize winners. Certainly, the Syme medallion aligns favourably with the bronze medallion in the portrait.

The photo to the right is of Dr George Baker, sourced from the linked document. It’s a pleasing likeness to the portrait.

The photo to the right is of Dr George Baker, sourced from the linked document. It’s a pleasing likeness to the portrait.

Jan Worthington reports of Dr Baker:

“He was born in Coventry, England on 10 October 1908. Very little can be found about his origins or arrival in Australia but it appears that he could have been adopted by the Sydenham family in Warwickshire. Henry Sydenham was a cooper. By 1925 was working as a junior assistant in the Geology School at the University of Melbourne.”

“George married Margaret Kathleen Mona (known as Molly) Chisholm (1903-1991) in Victoria in 1950. In 1963 he was living at Glenhuntly and was recorded in electoral rolls as a Research Officer. His wife was a bookkeeper. George is described as a retired Doctor of Science when he died at Point Lonsdale on 30 May 1975.”

George Baker shared the Syme Prize for Scientific Research in 1944. In 1956 the University of Melbourne conferred on him the degree of D.Sc., its most prestigious degree in science. George was a Fellow of the Mineralogical Society of America and the Meteoritical Society, a Life Member of the American Geophysical Union, the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain, and the Royal Society of Victoria, and a Foundation Member of the Geological Society of Australia. He was Commissioner for Australia of the International Committee on Meteorites of the International Geological Commission.

The silver medallion to the left of the David Syme Prize medal is revealed to be the Royal Society of Victoria’s own Medal for Excellence in Scientific Research – the first ever awarded, in 1959, to Dr George Baker. Leonie further observes:

The silver medallion to the left of the David Syme Prize medal is revealed to be the Royal Society of Victoria’s own Medal for Excellence in Scientific Research – the first ever awarded, in 1959, to Dr George Baker. Leonie further observes:

“It seems a bit sad that there is hardly any information about him from Australian sites. The best information I found online was the memorial in American Mineralogist. Yet he spent most of his life in Victoria, with much of it at University of Melbourne going from junior assistant to student, to graduate, then to academic. He was Senior Principal Research Scientist of CSIRO Mineragraphic section. He donated a sizeable collection of mineral specimens to the National Museum of Victoria where he was Honorary Associate in Mineralogy. Aside from the David Syme Research Prize and inaugural Royal Society of Victoria medallist, he was also a founding member of the Geological Society of Australia.”

“Perhaps the unearthing and identification of this portrait provides a good opportunity to publish a piece about his life and contribution to science. There are probably still people alive today who worked with him. I’d suggest contacting the institutions he was closely associated with to see if they can assist.”

Confirmation!

As it turns out, help was indeed close at hand in the form of another RSV Fellow, Dr Thomas Darragh, a Curator Emeritus with Museums Victoria and a life member of the Royal Society of Victoria.

“The portrait is of Dr George Baker, former member of the Society. In his will, he left the portrait to the Society and his collection to the Museum. I picked up the collection from his home a few days after he died in 1975 and also I think the portrait… I think you will find the medal is the RSV research medal. The portrait used to hang on one of the walls but must have been taken down during renovations. I thought it was labelled. The portrait was painted after he received his DSc from Melbourne Uni, hence the doctoral robes.”

Congratulations are in order to Anne Donald and Leonie Kirchmajer, who cracked the case! In line with Leonie’s recommendation, we will look to how the Society can celebrate Dr Baker’s contributions to science in Victoria as an early achiever in our post-war research era. Meanwhile, our grateful thanks to all those who spent time and effort in helping us piece the puzzle together; most appreciated.