Citizen Science – Collaborations between Scientists & Communities

By Scott Reddiex & Catriona Nguyen-Robertson

Science is about understanding the amazing universe in which we live. It involves making observations, developing hypotheses based on data, testing them with experiments, and using the results to gain a better understanding of the world – from an infinitesimally tiny scale to the size of the universe itself. A central component of the scientific method is the collection of data, the “life blood of science”, which can involve something as complex as colliding atoms in a particle accelerator, or simply taking a photo of an insect in your backyard.

Science is about understanding the amazing universe in which we live. It involves making observations, developing hypotheses based on data, testing them with experiments, and using the results to gain a better understanding of the world – from an infinitesimally tiny scale to the size of the universe itself. A central component of the scientific method is the collection of data, the “life blood of science”, which can involve something as complex as colliding atoms in a particle accelerator, or simply taking a photo of an insect in your backyard.

The Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) is an online repository of scientific information that tracks biodiversity in space and time. Akin to an online museum, the ALA comprises data from a variety of sources, such as biodiversity atlases, collections, museum records, and many others. While museums contain copious quantities of data in the form of samples and records, their data is limited to snapshots of the past, leaving gaps in our knowledge about the current composition of ecosystems. When you capture a photo of a native bee in your backyard, the quick snap with your digital camera records three key pieces of data: the appearance of a particular insect, in a specific location, at a precise moment in time. All from a single photograph, these pieces of information can inform our understanding of that insect, and the broader ecosystem we share. This simplicity is the power that citizen science has.

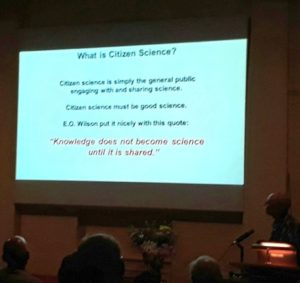

Citizen science is the collection and analysis of scientific data by anyone and everyone, with collaboration from professional scientists. One of the professional scientists who has embraced the use of citizen science in Australia, particularly in the area of biodiversity and entomology, is Dr Ken Walker.

Dr Walker is an entomologist and passionate taxonomist and has been the Senior Curator of Entomology at Museums Victoria for over 36 years. Like many of our speakers, his love for science was sparked at a young age. Every weekend he went birding with his father and travelled often as part of his father’s work, which fostered his love of nature and a desire to work out in the field. Dr Walker went on to study agricultural science, during which time he realised that entomology and taxonomy was his calling in life while writing an essay on the two-spotted mite. He found that he genuinely enjoyed researching, learning and writing about the mite, and hasn’t stopped researching insects since, having now personally named over 200 insect species.

Our picture of biodiversity is a jigsaw puzzle with many missing pieces – with 74 million records, the ALA lists many species with no images or additional information. It’s a puzzle that Dr Walker is aiming to solve, with help from the increasing number of citizen scientists around Australia. Having previously created the Museum Victoria Bioinformatics website (making more than 500,000 of the museum’s data records available to the public) and the Pests and Diseases Image Library (‘PaDIL’, providing images and information of over 4,000 plant and insect pests for quarantine and biosecurity), and with a passion for scientific engagement, Dr Walker was perfectly skilled to create a new citizen science platform. In 2013, with funding from Museums Victoria and the Atlas of Living Australia, Dr Walker created an Australian citizen science repository website called BowerBird (www.bowerbird.org.au).

BowerBird is a repository website for people to upload photos they take of wildlife, where they are viewed by entomologists, ecologists, and other scientists to identify the species, assess biodiversity in specific areas and to record sightings over time. The information gathered from both museum data, accessible through the ALA, and citizen science repositories, such as BowerBird, together can provide the missing pieces and keep our knowledge of ecosystems up-to-date. One exciting example of the strength that BowerBird has involves a little ladybird, Micraspis flavovittata, which only had museum records from 1874 and 1949. With no documented sightings in over 50 years, the species was assumed to be extinct. That was until one day in 2016, when an image taken by a photographer in Portland, Victoria, was uploaded to BowerBird and identified as being the “extinct” Micraspis flavovittata. As far as our scientific knowledge was concerned, the ladybird had come back from the dead – an example of a record righted by citizen science.

Photos uploaded to the repository not only record the existence of particular species, but also how they interact with each other and their environment. A fascinating example that Dr Walker gave was of a species of leafcutter bees (Megachile macularis), which were long thought to build leafy brood cells underground in disused burrows. Over the course of three days, a BowerBird contributor from Emerald, Queensland, photographed a leafcutter bee flying back and forth, taking cut leaves and pollen into a burrow that was less ‘disused’ and more ‘the home of a wolf spider’. While this alone contradicted the textbooks, there was no sign of aggression from the spider, and this has now become the first evidence for co-habitation of a leafcutter bee with an arachnid that was previously assumed to be predatory.

The contributions of citizen scientists to the BowerBird repository can additionally play an important role in quarantine and biosecurity. After taking a photo of a praying mantis in his mother’s backyard in Geelong, Victoria, one citizen scientist uploaded the image to Bowerbird with the time, date and location data. After doing so, it was viewed by entomologists and determined to be the South African mantis – an invasive pest which, until then, had not been seen on Australian shores. While the biosecurity of the Australian border is among the toughest in the world, it may be citizen scientists who first detect the presence of any biosecurity breach such as this by the parasitic varroa mite, which is currently decimating bee populations around the world. When the parasite does eventually make it to Australia, the data uploaded by beekeepers could play a significant role in whatever management plan is devised.

You can visit Dr Ken at the Melbourne Museum, where the ‘Bugs Alive!’ exhibition has a regularly rotated selection of the massive insect collection held by the museum on display. If the idea of citizen science has piqued your interest, you can get involved and read more about BowerBird on their website. Then the next time you spot interesting wildlife, take a photo and upload it, because as has happened before: it may well be the only living record of it!