Everybody Be Cool: Using Community Spaces to Manage Heatwaves

By Shirley Diez, Fran Macdonald, and Phani Harsha Yeggina

This article provides an overview of work recently delivered by the Western Alliance for Greenhouse Action (WAGA), a partnership of councils in the west of Melbourne, with support from Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) and Yarra Energy Foundation (YEF). The project included selection and assessment of a range of community buildings, views from the users of these spaces, and preliminary discussions about management of such spaces during heatwaves.

Coming into summer, how can we look after people who can’t stay cool at home? Where can they go? What would be needed to ensure everyone stays safe in a heatwave? Greater Melbourne’s Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy1 funded a project called ‘Creating a Network of Safe Spaces for Extreme Heat Events’ to explore what is needed to make a network of heatwave safe community buildings for vulnerable people within the Greater Melbourne Region.

Record heat around the world

A quick news scan shows that the northern hemisphere has experienced record-breaking heat in summer this year, with built-up areas additionally impacted by the ‘Urban Heat Island Effect’.2,3

In Australia, heatwaves are one of the most powerful and dangerous natural disasters that lead to increases in heat-related hospital admissions and deaths.4,5,6 While extreme heat can cause physical illness and death, it can also contribute to mental illness, and increases the risk of violence.7,8

Some cohorts are particularly vulnerable, and so designing multi-faceted approaches to limit the impact of heatwaves on individuals and communities is vital.

Unlike floods and fire, there is limited practical, place-based experience around managing heatwave emergencies in Victoria. The guiding document is the State Extreme Heat Subplan, under the State Emergency Management Plan (SEMP), which outlines how agencies respond to the impacts and consequences of extreme heat and heatwaves. To test our preparedness, some organisations have started bringing together people from the health and community sectors, the emergency sector, state and local government, and industry.9,10,11

While there are many organisations involved,12,13,14 our project’s focus was on the most vulnerable and at-risk people and the role of local governments and community buildings in supporting these people in the event of an extreme heat event.

Where do Melburnians go when it’s hot? What do they need?

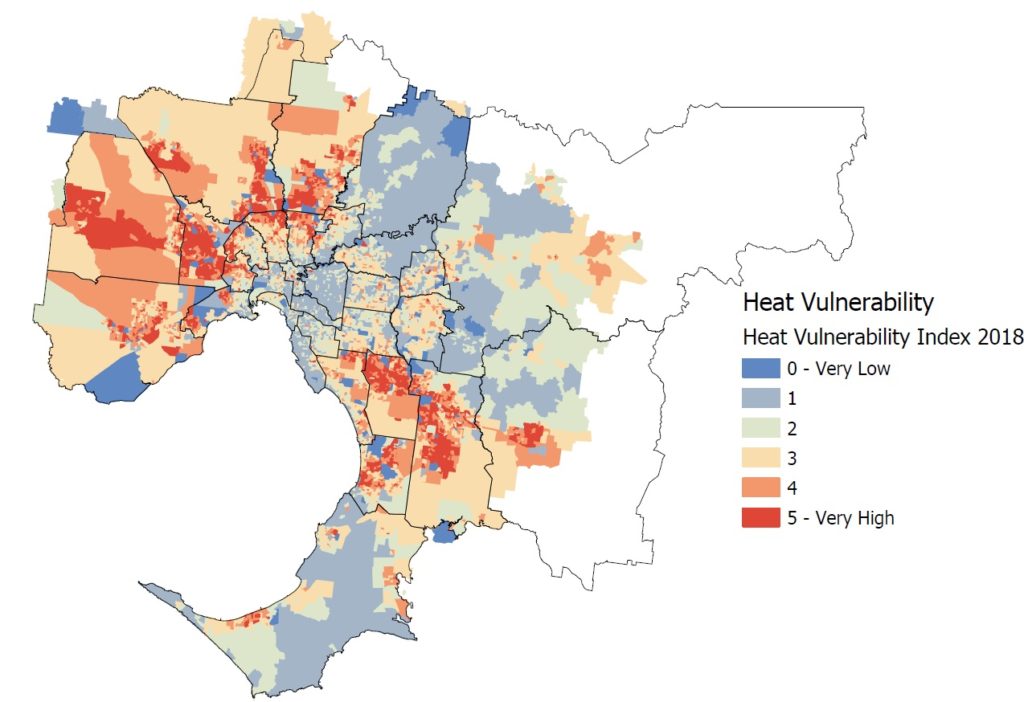

To understand where to focus attention in Melbourne, we can examine a heat vulnerability map, produced by the Victorian government by overlaying heat and census data.15 The map shows that some parts of Melbourne are hotter and more likely to include at-risk people.

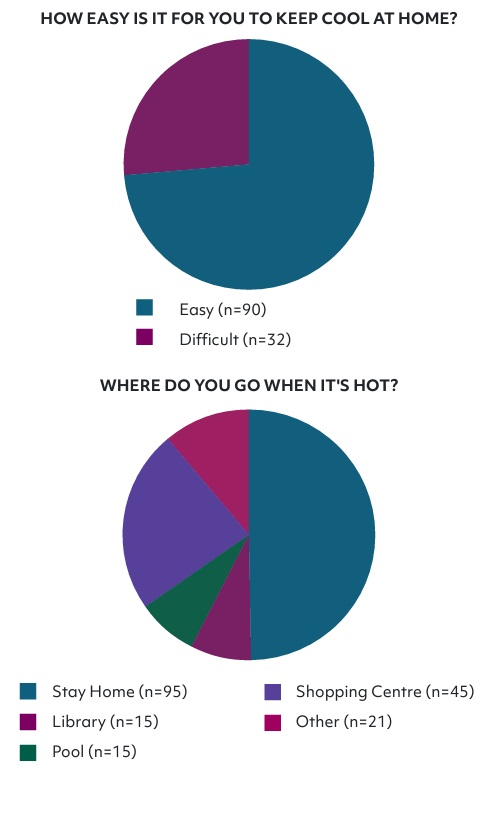

To find out what people do in hot weather, we collected the results of over 120 conversations with people on the street near libraries and visiting neighbourhood and community houses in Melbourne’s west. While three quarters said it was easy for them to keep cool at home in summer, the other quarter found it difficult. On really hot days, roughly half of the respondents stayed home, while half went to places like shopping centres, swimming pools, libraries, and friend’s homes.

The requirements of a ‘cool space’ were very simple: somewhere to sit, bathroom facilities, and cool water to drink. A range of other small comforts were identified as being useful, such as Wi-Fi or other entertainment, maybe some snacks, and tea/coffee. These are all things that could potentially be provided by community buildings.

How could community buildings play a role?

Community buildings play a crucial role in the day-to-day life of a community. Libraries, community centres, and recreation and leisure centres are the most frequently used public infrastructure within council areas. In times of extreme weather events, such as floods, bushfires, or other emergencies, these buildings commonly act as a safe haven for people. During heat waves, community buildings could similarly play a vital role in providing a cool space for people, especially for those who cannot avoid the heat at home. Importantly, some community buildings like libraries and neighbourhood houses have existing networks that could potentially support a coordinated response.

In 2022, our project assessed community buildings in Melbourne’s west to identify heat-related vulnerabilities of buildings and collect information on the most common users of these buildings. Councils selected buildings based on factors such as the presence of air conditioning, accessibility to different transportation options, geographic location in relation to other buildings, and proximity to heat-vulnerable populations. Community centres, neighbourhood houses, and libraries were the top choices, followed by recreation centres, town halls, senior citizen centres, and one place of worship.

During early conversations with building managers, we learned that some of the buildings already serve as a cool space during extreme heat for people of all ages, with a higher proportion of seniors. Some buildings also provide a safe space for some of the most vulnerable people in the community, including those experiencing homelessness and domestic violence. It became clear that community buildings are already seen as cool spaces by many community members, and that they will play a larger role as communities adapt to climate change.

But each “safe haven” isn’t perfect. The most common building vulnerabilities identified in our project include the absence of backup power, exposure of air conditioning systems to hot sun, absence of external shade trees, and the lack of building elements such as insulation. Costs to address the vulnerabilities range from inexpensive (e.g., draught sealing, shade cloth) to more capital intensive and complex upgrades (e.g., relocation of heat rejection equipment and improving structural condition of the building).

Key questions and challenges

As the project was led by local governments, an initial question was “What is the role of a local council in providing cool spaces?”. We recognised that councils are front-line service providers and managers of community buildings, especially for vulnerable residents, but this role varies across internal departments or units. Sustainability units coordinate their councils’ overall response to climate change impacts such as heatwaves; emergency management units coordinate responses and preparation for extreme weather events; health and community care units manage services on the ground; and facilities teams manage the maintenance and upgrade of buildings.

Our solution for the project was to set up a working group involving all the various teams, including managers of community centres themselves, such as neighbourhood houses and libraries.

The working group identified the following:

- Many types of community buildings could support the community in a heat emergency, but not all can be easily upgraded. The most suitable, such as libraries, are already being used by the community. These are often already set up to cope with heatwaves, at least to a certain extent; for example, by providing a cool environment for people to sit in for hours at a time.

- Some potentially suitable buildings require expensive upgrades to improve them, such as new air conditioning (HVAC) systems or insulation. These improvements may only be considered cost-effective as part of a more general upgrade, or when compared to the costs already associated with extreme weather events, such as increased hospital admissions. Heatwaves have a significant financial impact on built assets like community buildings, with damages projected to more than double by 2050.16

- There are many practical considerations for the operation and use of community centres during heatwaves. They include operating hours, staffing needs, transport and travel corridors to and from centres, whether to accommodate pets, and so on. Neighbourhood and community houses managers also mentioned increased energy costs that would be associated with running air conditioners for longer.

- Services across councils vary, so it is essential to create clear and accessible messages about what spaces may be available for people during heatwaves. There could be confusion if some councils or authorities advise people to stay home.

- A council could potentially coordinate messaging and services during heatwaves within their own municipality, but regional coordination (across municipalities) would be harder. This may require participating councils to set up a central coordinating mechanism or even shared services.

Insights

Despite the challenges, we have found that it is possible for community buildings to provide significant assistance during heatwaves to at-risk people, and some of the best solutions are not expensive. Some of the solutions involve modified operating hours, changes to staffing, and provision of heatwave safe kits for residents to take home. Following on from our project, the kits are already being produced by some councils and include items such as neck coolers, taxi vouchers, cooling towels and reusable drink bottles. Other actions involve adjustments to buildings like insulation, external shading, and ‘cool-scaping’.

What next?

Addressing heatwaves is one of the most urgent climate change adaptation challenges for everyone, so it needs to be everyone’s business.

Understanding the places people go during extreme weather events and how they use them is critical, as it can inform the potential for surge capacity at these centres. Clarity about roles, responsibilities, communication, and local coordination is also important, and would support those who work with our community’s most at-risk groups. We recommend that community service organisations consider developing heat plans for themselves, and explore how a heatwave might play out in their neighbourhood.

Our project has shown that it is possible for community buildings to provide significant assistance, for a relatively small cost. While there is still uncertainty about the roles of councils, other community support organisations, and community buildings during heatwaves, we feel confident that the findings of our work can inform future discussions. We’ve shown that at-risk people visit community buildings like libraries and neighbourhood houses during heatwaves, that some low-cost improvements can be made to those buildings and that there is a willingness to work together in situ to develop local heat approaches. It is important to keep advocating for these community buildings that provide many benefits to their community.

If you don’t have a means of staying cool at home in the summer heat, consider seeking community buildings – a library, a recreation centre, a neighbourhood house, etc. They are typically already set up to be cool on a hot day, and they provide a space for recreation, to learn, to connect, or to “beat the heat”.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank the team at Network West who assisted by collecting local views about heat, Northern Alliance for Greenhouse Action for extending the project to the north, the 16 local councils and their officers who contributed their ideas and time selecting buildings and discussing their use. We also extend our thanks to Sweltering Cities for their insights and for continuing the conversations nationally.

–

Shirley Diez is a Program Manager at Victorian Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. She has supported and coordinated the delivery of state government projects and discussions about environmental and climate-related issues for more than two decades.

Fran Macdonald is the Executive Officer of WAGA, which includes Brimbank, Hobsons Bay, Maribyrnong, Melton, Moonee Valley, Moorabool, and Wyndham Councils. WAGA is also leading a broader project called ‘Victorian Climate Resilient Councils’, to develop an ongoing program of support for councils to understand and embed climate change adaptation across all their services, operations, and assets.

Phani Harsha Yeggina worked as Building Resilience Project Officer at the Yarra Energy Foundation during the delivery of this project. He has deep knowledge of issues surrounding climate change and is passionate about finding equitable and just solutions to the problems.

References:

- Greater Melbourne Regional Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (2021). climatechange.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0043/549799/GreaterMelbourneRegionalClimateChangeAdaptationStrategy.pdf

- Extreme weather sweeps the world in “hot and dangerous weekend.” (2023, July 16). ABC News. abc.net.au/news/2023-07-16/extreme-heat-sweeps-the-world-from-europe-to-the-us-and-japan/102607620

- Scorching “new normal” as world buckles under extreme heat: WMO | UN News. (2023, August 18). News.un.org. news.un.org/en/story/2023/08/1139867

Doctors for the Environment Australia. (2020). Heatwaves and Health in Australia Fact Sheet Impacts of Heatwaves on Society. dea.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/DEA-Fact-Sheet_HeatwavesWEB.pdf

- Thomson, T. N., et al. (2023). Population vulnerability to heat: A case-crossover analysis of heat health alerts and hospital morbidity data in Victoria, Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 100092. doi.org/10.1016/j.anzjph.2023.100092

- Victoria’s Future Climate Tool – case study. Stress testing for the potential impact of heatwave on Ambulance Victoria. (2023). climatechange.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/526024/Ambulance-Victoria-Case-Study-Victorias-Future-Climate-Tool.pdf

- Feeling the Heat. Victorian Council of Community Services (2021). vcoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Feeling-the-Heat.pdf

- Lander, J., et al. (2019) Extreme heat driven by the climate emergency: impacts on the health and wellbeing of public housing tenants in Mildura, Victoria. malleefamilycare.org.au/MFCSite/media/PDFDocuments/PublicHousing/2019/MalleeFamilyCare_PublicHousing_Report_2019.pdf

- The Greater Melbourne Heat Alliance: a new network of organisations and professionals working on addressing extreme heat impacts in Melbourne and supporting vulnerable communities.

- The Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (WSROC) and Resilient Sydney are also grappling with similar issues and are developing a Heatwave Management Guide in partnership with councils.

- City of Greater Dandenong ‘Prepare for a Heatwave’ emergency management exercise was held in September 2023.

- Heat Health Plan for Victoria. (2021). health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/heat-health-plan-for-victoria-2021.docx

- Local Government Climate Change Adaptation Roles and Responsibilities under Victorian legislation. Guidance for local government decision-makers. (2020). Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victoria.

- Planning for extreme heat and heatwaves. (2020). Department of Health, Victoria. health.vic.gov.au/environmental-health/planning-for-extreme-heat-and-heatwaves

- Metropolitan Melbourne Heat Vulnerability Index 2018 – Victorian Government Data Directory. (2023.). DataVic. Retrieved November 14, 2023, from discover.data.vic.gov.au/dataset/metropolitan-melbourne-heat-vulnerability-index-2018

- Natural Capital Economics (2023). Adaptive Community Assets: A report prepared for the Eastern Alliance for Greenhouse Action. eaga.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Adaptive-community-assets_Final-report-1.pdf