Science Communication is Everyone’s Business

Dr Simon Torok,

CEO and Director, Scientell

One of my favourite things about science communication is running a business. Let me explain.

In 2015, I founded the science communication consultancy Scientell Pty Ltd with Paul Holper. Scientell now comprises three other science communicators (Alysha Huxley, Dr Cintya Dharmayanti, and Sonia Bluhm), administrative staff, and over a dozen specialist subcontractors, including editors, designers, photographers, videographers, and animators.

Sadly, Paul died in September. While we greatly miss Paul’s contribution to the Scientell team, and his generosity as a leader and friend, Scientell continues to have a lasting legacy in science communication.

How did we start, what did we accomplish, and what lessons did we learn along the way?

Origin story

I first met Paul 30 years ago at the Greenhouse 1994 climate change science conference, which he had organised in New Zealand. I was a student, finishing my PhD in climate change research, and Paul patiently answered my questions about how to succeed in science communication and get a job like his.

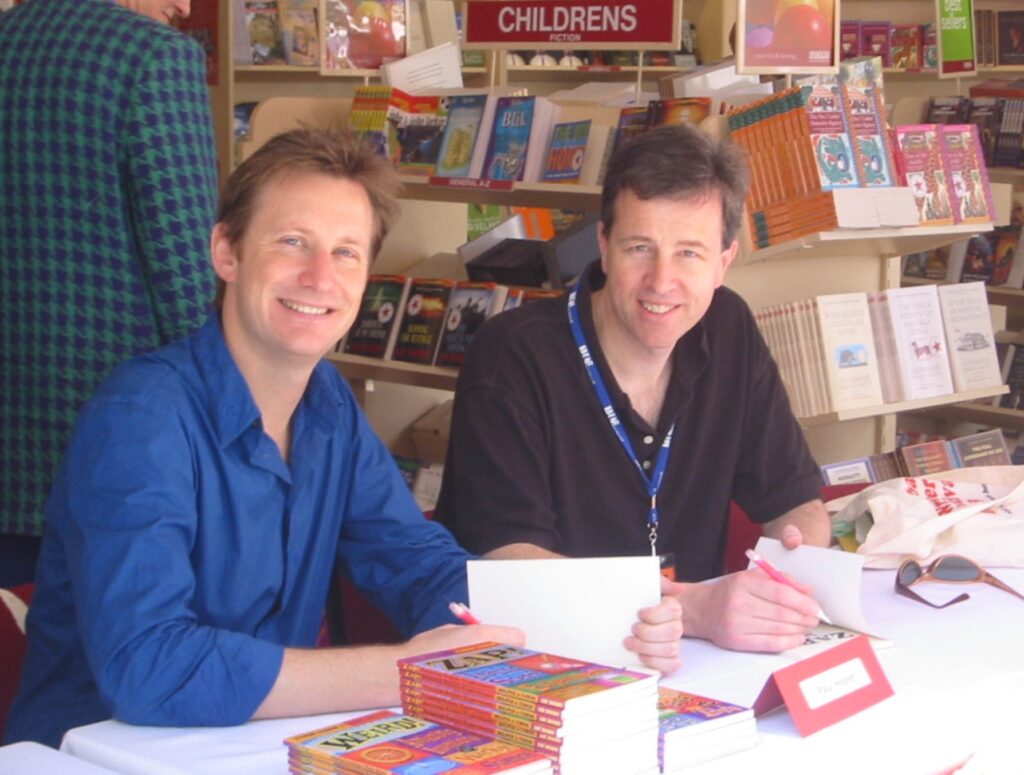

Our paths crossed again in 1996 when Paul was the communication manager for CSIRO Atmospheric Research, and I started as the communication manager for CSIRO Environmental Mechanics. A couple of years later, Paul suggested we write a science trivia book together, which was published by ABC Books in 1999.

Each year for the next 20 years we wrote one popular science book a year for a range of publishers, including Pan MacMillan, Oxford University Press, and CSIRO Publishing. This was in our spare time, while Paul worked for CSIRO in Melbourne, and I worked in Canberra, then England, and then also at CSIRO in Melbourne. Many of the books were for children, and some were translated into Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Korean, and Hungarian.

The efficient, spare-time writing one book on average each year laid the foundation for Scientell.

Scientell: science, in other words

Scientell is a science communication company that seeks to maximise the impact of science. We work closely with clients to transform their scientific and technical information into clear messages for non-scientific audiences such as policymakers, young people and the wider community.

We distil and synthesise science into clear and usable knowledge via various publications, such as brochures, factsheets, booklets, books, newsletters, reports, and education material, as well as presentations, websites, videos, animations, and infographics. We also have experience in communication planning and implementation, development of strategic plans, workshop facilitation, and communication training.

Over the past nine years, Scientell has worked on over 350 projects for clients including universities and research centres, Commonwealth, state and local government, CSIRO, and private companies. In addition, before founding Scientell, I worked at senior levels in science agencies and contracted consultants. So I’ve looked at consulting from both sides now.

Through our work, we aim to increase the accessibility, enjoyment and impact of science. We work on projects that enhance the impact of science, research and technology with evidence-based, accessible communication activities and products provided in an approachable way.

We aim to tell a good story, framing information in ways that appeal to people’s values, while basing the content on robust and credible evidence. We consider what the audience needs to hear more than what scientists want to say. Rather than simplifying, our work is about clarifying – it’s not about dumbing down or dulling down; it’s about using clear, jargon-free language while maintaining the integrity of the information, and the excitement of the science.

Scientell won the microbusiness category of the Monash Business Awards in 2016-17, and has been shortlisted as a finalist for the Australian Small Business Champion Awards. We’ve had articles included in The Conversation Yearbook 2019 and The Best Australian Science Writing 2017.

9 points in 9 years: what we’ve learned along the way

Paul noted nine things he learned in his first year of our business, as he transitioned from the corporate world to company director.

- Establish a workspace, ideally a dedicated office. It helps you focus on work, and you don’t want to waste time gathering your resources each time you start work.

- Develop a routine. Commuting to a workplace imposes structure on your work life.

- Maintain networks and socialise. Have regular catch-ups with colleagues and former workmates. These meetings are part social and part business.

- Reach out and contact at least one person each day. It’s good for business, good for networking, and good for the soul. It might be a phone call or simply an email forwarding interesting information.

- Attend events. Be known and keep up with advances in science and science communication. Look out for relevant workshops and conferences.

- Collaborate. Working with others is often more productive (and more fun), and including others in project pitches increases your chances of success.

- Join and participate in professional groups, such as the Australian Science Communicators.

- Get a good accountant, bookkeeper, and lawyer. Setting yourself up properly maximises your chances of success. Find people you trust.

- Invest in software for accounting, editing, project management and file management.

We’ve also noted nine tips for running a sustainable science-based business:

- Choose your team members wisely. In a small business, you need to ensure the team shares the same values, has a strong understanding of scientific processes, and demonstrates good interpersonal skills.

- Manage the peaks and troughs of a small business through planned business development activities. Know which months are generally quieter and plan business development activities in advance to bring in business.

- Understand your market, and price your products and services accordingly. NGOs and local governments have different budgets to private companies, and governments all have different procurement thresholds.

- Ask the client about their budget range when quoting, as doing so can avoid misunderstanding about the size and scope of the project.

- Once contracted, help your client understand what they need from the project by clarifying the scope, objectives, and precisely what the end product(s) will look like.

- Always look for ways to improve your client service and expand the job: have a continual improvement mindset, and consider what else you can do to help the client.

- Consider yourself part of the team in the organisation that is employing you. Your client should see you as part of the team and treat you like colleagues, not outsiders.

- Define your audience(s). A campaign for multi-million dollar funding will be very different from an internal awareness-raising project. And don’t just call the audience the ‘general public’; there’s no such thing.

- Advocate for the importance of science communication in science. It is not an add-on at the end, but an essential and integral ingredient in science (see below).

Top takeaways about communicating science

I’ll conclude with my three sound bites about the science communication domain.

- Science communication isn’t rocket science – it’s communicating rocket science, which is just as hard. Science communication is difficult and needs to be approached professionally and respected as a profession.

- Science communicators aren’t saving the world – we’re helping the people saving the world to save the world. Science communicators help by ensuring science has impact. As a communication professional, you have a lot of value to add – such as providing advice on how to increase impact, getting people to think about their audience rather than themselves, and providing expert help and facilitating scientists’ communication.

- Science communication isn’t the icing on the cake, it’s an essential ingredient in the cake. Science communication shouldn’t just come at the end. It’s integral to science, needs to be there from the start, and has to be a part of how science is done. The science cake won’t taste as good if this essential ingredient is omitted.