The Art of Policy Upcycling

By Dr Natasha Abrahams

Strategy and Government Relations Manager,

Australian Academy of Technological Sciences & Engineering (ATSE)

In the op-shop of science policy, one can hunt through the bins for a bargain or a treasure. Some ideas may need a simple repair or a refresh to become fashionable again, while others have been discarded for a reason.

As a policy professional at the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (ATSE), I rely on the work and wisdom of both my peers and those who have come before me. Due to the cyclical nature of policy, those who work in this space become adept at remixing the ideas that have come before into new solutions for current issues.

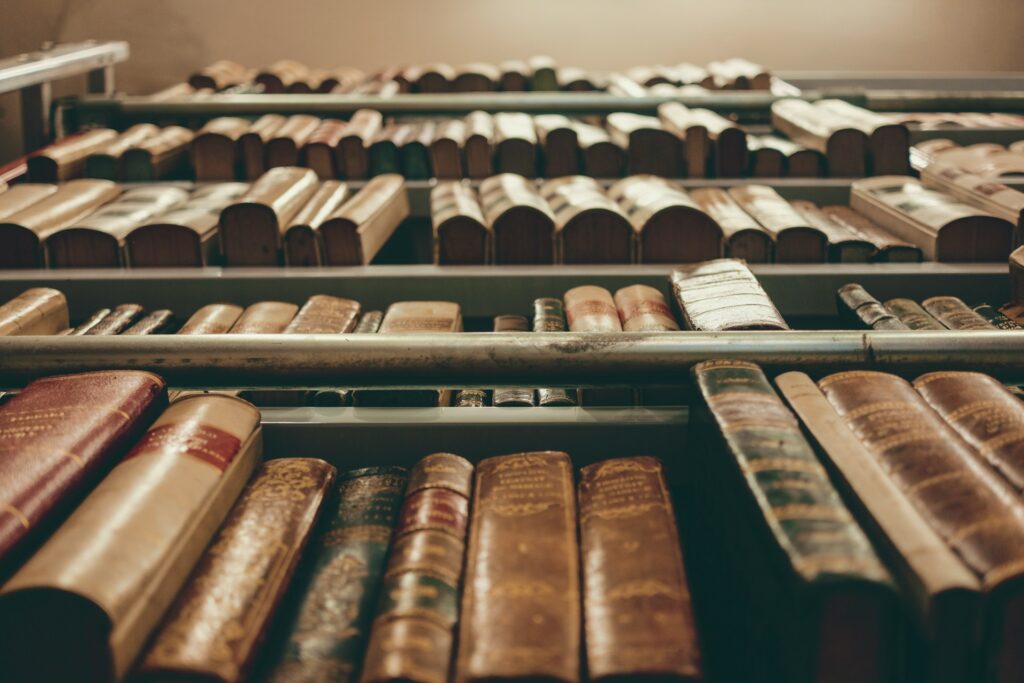

I was struck by this when sorting through ATSE’s physical archive of submissions, reports and conference programs. Although these publications dated back decades, many could be submitted to recent inquiries with little more than a date change on the cover sheet.

ATSE’s submission to a 2009 inquiry into the Australian Research Council called for a greater focus on interdisciplinary collaboration, noting that research questions of the future will need an interdisciplinary approach, but funding structures do not accommodate this.1 The need for research funding to support and incentivise interdisciplinary research remains a staple of science policy circles today, and I am sure it was not a revolutionary idea fifteen years ago either.

A qualified success

The challenge for science policy professionals is how to present these ideas – often very good ideas that have been floating around the sector for a long time – in a way that is compelling and timely for today’s decision-makers.

This can be difficult when there is no good reason that an idea was not adopted, and its political moment has passed. For instance, and much to the chagrin of many in the education policy space, the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) review recommendations have never been implemented.2 The AQF Review final report, developed by an expert panel chaired by the late Prof Peter Noonan, was the result of considerable consultation with the education sector.

The final report laid out a framework for modernising and simplifying the AQF, aligning qualifications from different types of education providers, and dealing with the then-thorny issue of micro-credentialing. This Grand Unified Framework would have been a favourable solution to some of the challenges plaguing the education sector. Of course, implementation is never without some pain, but there was broad agreement that it had to happen.

Unfortunately, timing was not in the AQF Review’s favour, with the final report being released in late 2019 and left to languish as other issues became more urgent. Recently, leading policy minds of the higher education sector have furthered the debate through the book Rethinking Tertiary Education.3 Now, five years after the publication of the AQF Review, the Universities Accord has attempted to revive it, recommending that its proposals be progressed through engagement with industry, unions and governments.

With 47 recommendations formally outlined in the Universities Accord, and the Federal Government approaching these reforms in tranches, it is hard to see when or if revamping the AQF will be on the agenda. By the time the AQF is revisited, it may even be necessary to conduct a new review, taking stock of the changes to the system since 2019, as well as considering the evolving needs of learners and employers.

Policy professionals and sector leaders will dust off old submissions, and the cycle continues.

Burning issues from history

As those in policy spaces will be aware, the best ideas often fail to gain traction because they are difficult, expensive, or both. Flicking through ATSE’s archives, I saw how this was the case for climate change policy, arguably the defining problem of our time. Decades-old publications and conference proceedings documented concerns from leading thinkers on how climate change might affect Australia in the future, and policy interventions for this great challenge.

Proceedings from a 1999 joint Academies’ seminar on bushfires – enthusiastically (perhaps insensitively) named ‘FIRE! The Australian Experience’ – outline the possibility of increased bushfires due to climate change.4 One chapter discusses predictive modelling for bushfire management, briefly mentioning its niche application of modelling the likely effects of climate change on fire occurrence.

The detailed exposition for each of these chapters indicates that we now have a higher level of presumed knowledge for topics like climate change and information technology. However, the concerns remain similar – and we have reached the imagined tomorrow that experts and policy advisors warned about. The solutions are often still politically difficult and invariably still expensive. If decision-makers had heeded the advice back then, we could be more advanced in climate change mitigation by now.

Learning from the past to shape tomorrow

While I may wish that experts and policy professionals had been more strident and convincing about their warnings decades ago, somehow overcoming the limitations of the political ecosystem, I can’t say we aren’t repeating those patterns now.

I consider it a great privilege to be working in this exciting area, translating old and new ideas from bright thinkers into digestible solutions. It is gratifying when this work makes an impact, however modest. Nevertheless, a future-me writing this article might feel frustrated over missed opportunities in today’s policy debates, big and small.

Today’s niche policy issues, such as quantum ethics, may become more salient in the future. Researcher Dr Tara Roberson has identified that little is known about the societal risks of quantum technologies, yet now is the ideal time to build the sector in a way that minimises these issues.5

Future policy professionals may lament the decisions knowingly made today. For current major policy issues, such as critically low research expenditure, in a few years from now we might wonder how such predictable outcomes were allowed to occur. Finding solutions will become more urgent. The silver lining will be that policy professionals need only look through the archives to find inspiration for ideas whose time has come.

References

- Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (ATSE). (2009). Response to ARC Consultation Paper: ARC Centres of Excellence for Funding Commencing in 2011. science.org.au/supporting-science/science-policy-and-analysis/submissions-government/submission%E2%80%94arc-centres-0

- Department of Education. (2019, October). Australian Qualifications Framework Review – Department of Education, Australian Government. Department of Education. www.education.gov.au/higher-education-reviews-and-consultations/australian-qualifications-framework-review

- Dawkins, P., et al. (2023). Rethinking Tertiary Education. Melbourne University Publishing.

- National Academies Forum. (2000). FIRE! The Australian experience: Proceedings from the National Academies Forum seminar 30 September – 1 October 1999. University of Adelaide, South Australia. acola.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1999Oct-NAF-Seminar_FIRE-The-Australian-Experience.pdf

- Roberson, T. (2023). Talking About Responsible Quantum: “Awareness Is the Absolute Minimum that … We Need to Do.” NanoEthics, 17(1). doi.org/10.1007/s11569-023-00437-2