The RSV and our partners host science and technology events in Victoria throughout the year including National Science Week.

Most RSV presentations are both in-person and live-streamed.

Come and join in future events or catch up on past events at rsv.org.au/videos.

Tour of The Royal Exhibition Building Dome Promenade and Afternoon Tea at the RSV

Members of RSV and Geography Victoria are invited to spend an afternoon exploring the Royal Exhibition Building Dome before a relaxing afternoon tea at RSV.

Science Victoria Magazine

A magazine for the science and technology community

The Royal Society of Victoria publishes regular articles to keep Australia’s science and technology community up to speed with activities, opportunities, issues and new developments.

We welcome contributions from our members, supporters and the community.

Latest Edition of Science Victoria:

Dec 2025

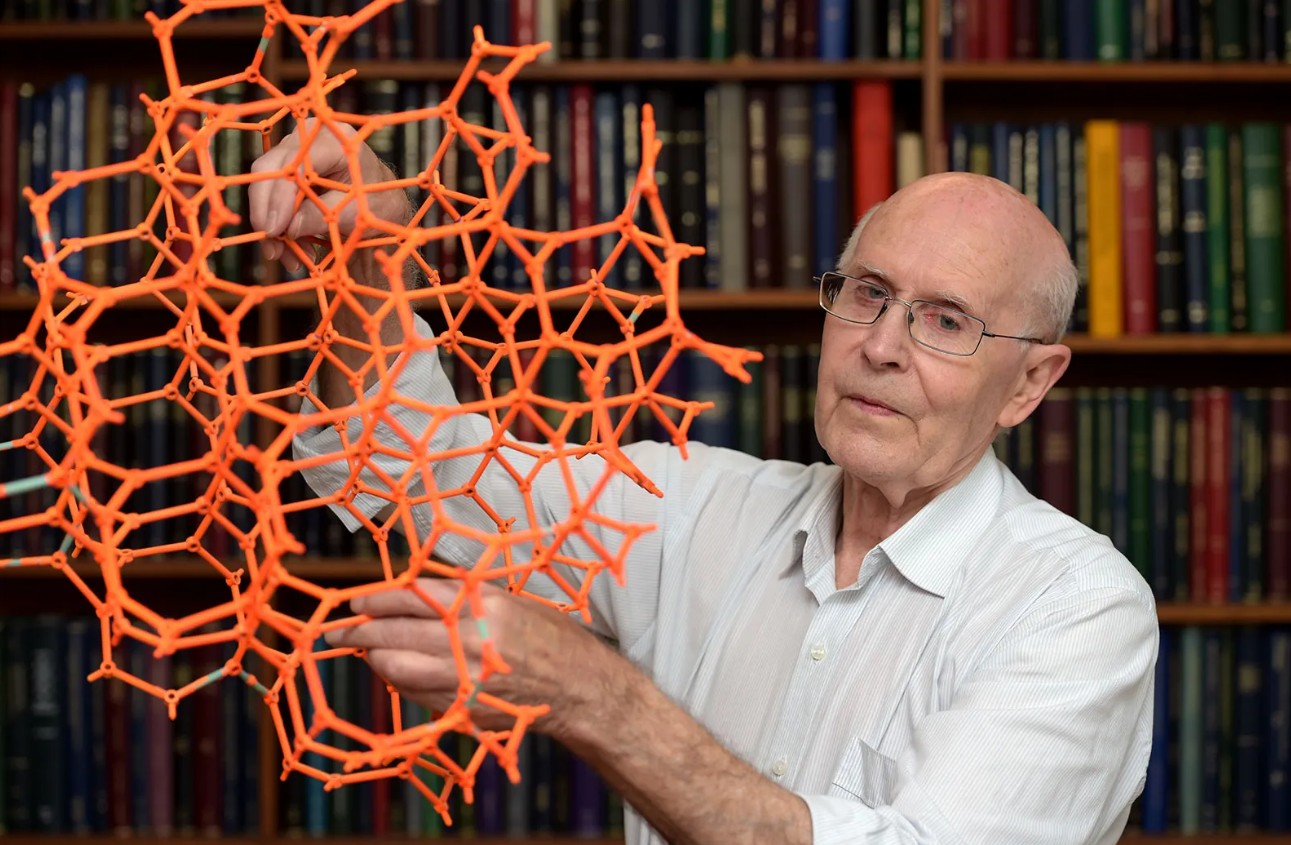

Victoria's Future Technologies

Technology is reshaping our economy, our society and our career opportunities faster than ever. In this issue we look at some of the future technologies that are reshaping Victoria and the people behind them.

What's on in Science and Technology

Get involved!

There's a lot going on across the science and technology community in Victoria and Australia. The RSV runs its own events and can support and promote yours.

Come along, participate and get involved.

Who we are

We are a vibrant physical and online hub where Australians with an interest in science and technology can meet to energetically share insights, trade ideas and discuss solutions to our society's important challenges.

We have been at the heart of Melbourne and Victoria's development since 1854.

A Place Where Science And Technology Meets

Whether online or in person, we are Victoria's science and technology hub. Come and attend one of our events, subscribe to our newsletter and Science Victoria magazine, or engage with others who share your interest in advancing science and technology.

A Community To Join

Membership of the Royal Society of Victoria is open to individuals and organisations across Australia and the region who are interested in science and technology.

A Location For Your Event

RSV Hall was built in 1859 and is a great heritage location for weddings, corporate events and business meetings. Hire all or part of our Melbourne CBD venue to make your next event one to remember.